John was born in 1939 in the small village of Beighton, Derbyshire, where his father was the local vicar. He left school at the age of 16; by then, with an abiding interest in all things mechanical, he had already bought his first car, an Austin 7, and stripped the engine down in his Blackheath bedroom. Cars, including fast and exotic performance cars, remained a passion throughout his life.

His first job was with J. Arthur Rank in the film industry, in due course becoming an editor and working on movies such as Spartacus. Film was in his blood from the beginning.

By the early 1970s he had become fascinated by clocks and started to dismantle them, learning and working on run-of-the-mill domestic clocks and developing an increasing knowledge and expertise. He progressed to some of the most famous makers, completely re-building a Tompion which when it came to him only the case, dial and front and back plates were original; he rebuilt the movement working merely on the positions of the original holes in the plates.

He was introduced to CAD (Computer Aided Design) while on a course at Paisley College in the late 80s. The day he found that computer software would allow him to draw a single tooth and array it around a circle to form a cog wheel “changed my life”, he claimed.

John was at heart a teacher and loved explaining clocks and their mechanisms. At a lecture at the Science Museum he used a sequence of CAD slides to explain William Hardy’s spring pallet escapement.

That was a breakthrough from the painstaking way it had been done previously, but he realized that if he could only animate the objects in his slides, the impact and educational value would be so much greater. Shortly afterwards he discovered the software that could do this. In its current form it is called Autodesk 3ds Max. He always wanted more from it and as the software’s capabilities developed over the years, so did John’s expertise. Even in his 70s he was a regular tester of its forthcoming “beta” releases and impressed much younger professional animators with his subtlety, his technical prowess – and particularly his ability to explain a complex mechanism by breaking it down visually to its essence.

Age certainly didn’t constrain him. He had become a legend at the annual European get together for serious 3D Studio Max users, where professional animators – young bloods in their 20s and 30s – who were advanced users of the software and making Hollywood film sequences or computer games scenarios, admired his animations and were astonished at the skills of this bearded 70-year-old; and he was always ready to learn from them, then take himself off to practise a new technique that might one day be useful.

He was equally at home using techniques and skills developed hundreds of years ago to restore an antique watch, as he was using the latest technology to film or animate it. Whatever the medium, he saw himself first and foremost as a craftsman.

As the technology grew so did John’s fascination with the medium. He was a consummate autodidact. Everything he did, he did with passion, energy and a commitment to doing it to the highest level of perfection. And he did indeed produce work at the very top of his field.

He expertly worked with some of the most important timepieces in history and, in later years used precise computer animation, blended with film making, to produce outstanding works that documented and explained exactly why some antique clocks were so important. He had a special talent for making complicated subjects easy to understand and appreciate.

To make a film needs a combination of many skills; graphic design, photography, motion picture filming; and of course 3d modelling and animation. But equally important to all these skills is the ability to "tell the story", to be able to explain complex mechanisms and principles in a clear and succinct way that can successfully engage an audience of varying ages and knowledge.

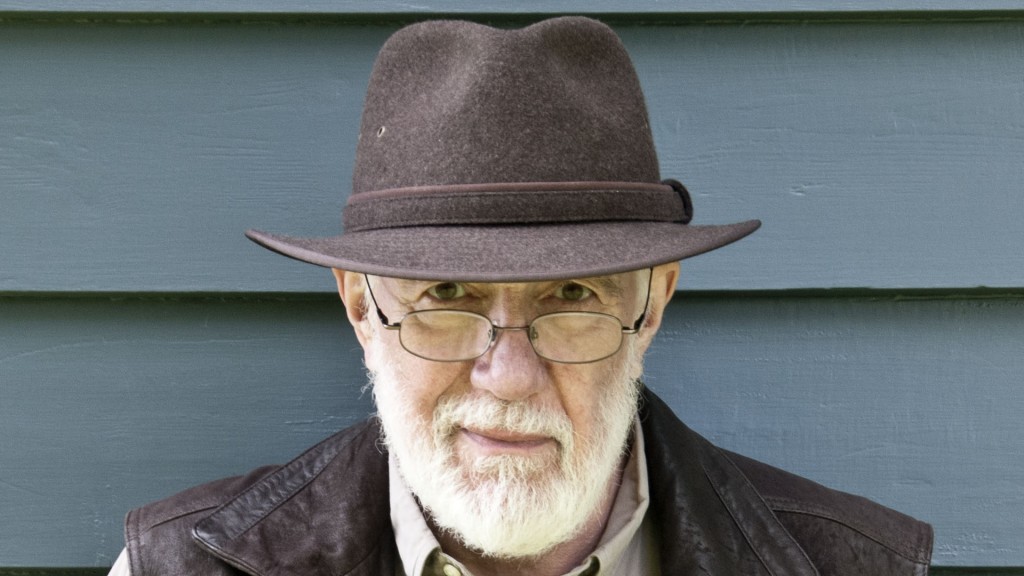

John Redfern

John transformed an old carriage house into state-of-the-art studios. He had separate workshops for clockmaking and restoration; woodworking (to repair clock cases); a computer studio with the latest animation technology; a photography studio with various cameras for close-ups and panning and a library full of horological books. He was completely self-contained and obviously lived a contented life with his wife Maxine.

Mostyn Gale, Clock Keeper & Conservator

The clock repair workshop

The photography workshop

The CAD workshop

John was a gifted clockmaker and restorer. His special skill was in combining two major disciplines: clockmaker and animator. He could walk in the shoes of a watchmaker and understand the complexity of what needed to be explained, and then with his animator's hat on, clearly and effectively animate the mechanics to show the process clearly even to a non-technical viewer.

Philip Whyte